Even gargantuan Jupiter, with its whirling superstorms and volatile temperatures, has a soft side. A team of researchers recently documented stellar winds from the Sun, squishing the planet’s magnetosphere and raising the temperatures in the planet’s atmosphere by 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius).

The team’s research, published today in Geophysical Research Letters, is the first to document this phenomenon—a burst of solar energy hitting Jupiter. That said, the scientists believe the solar beatdown occurs a few times each month.

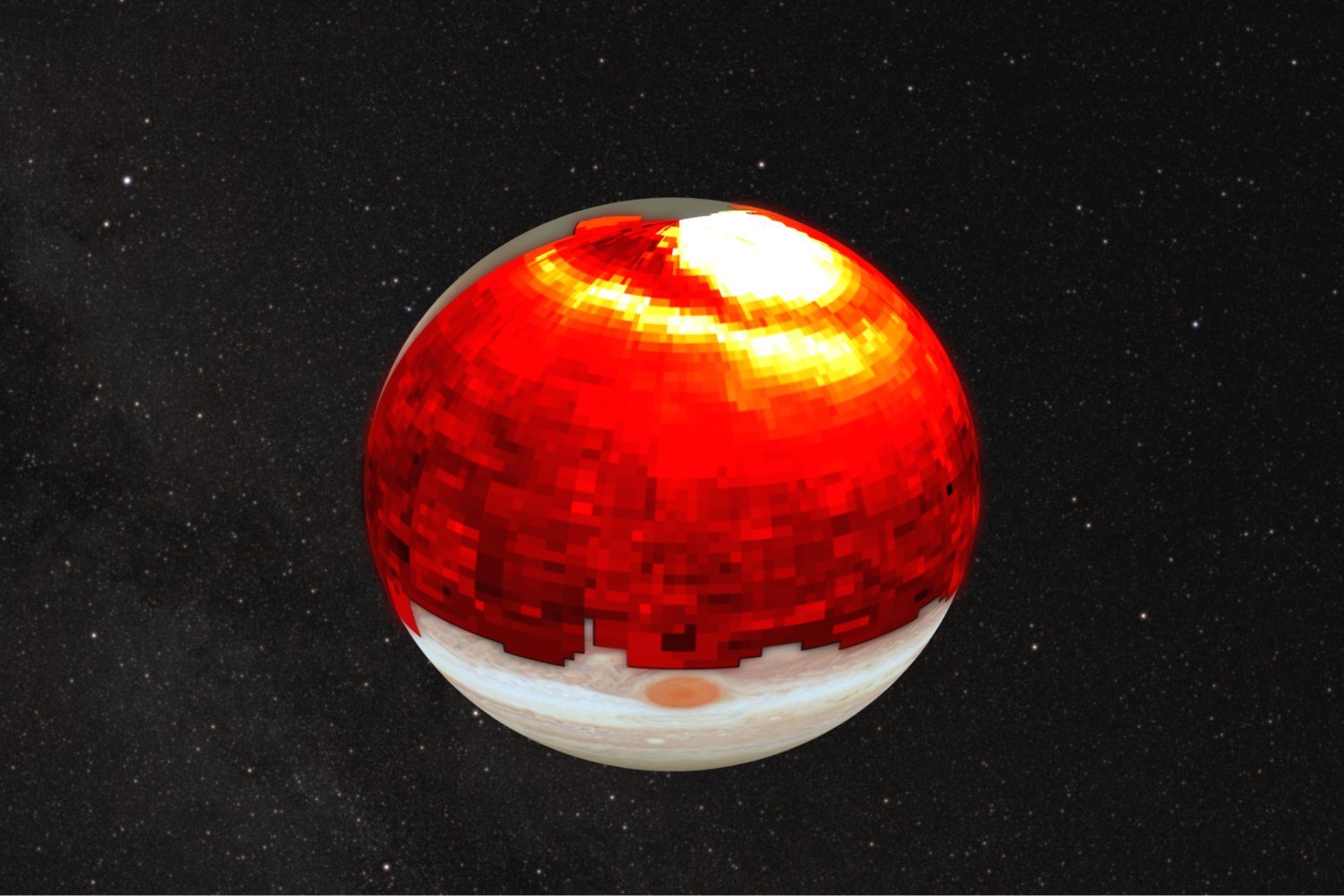

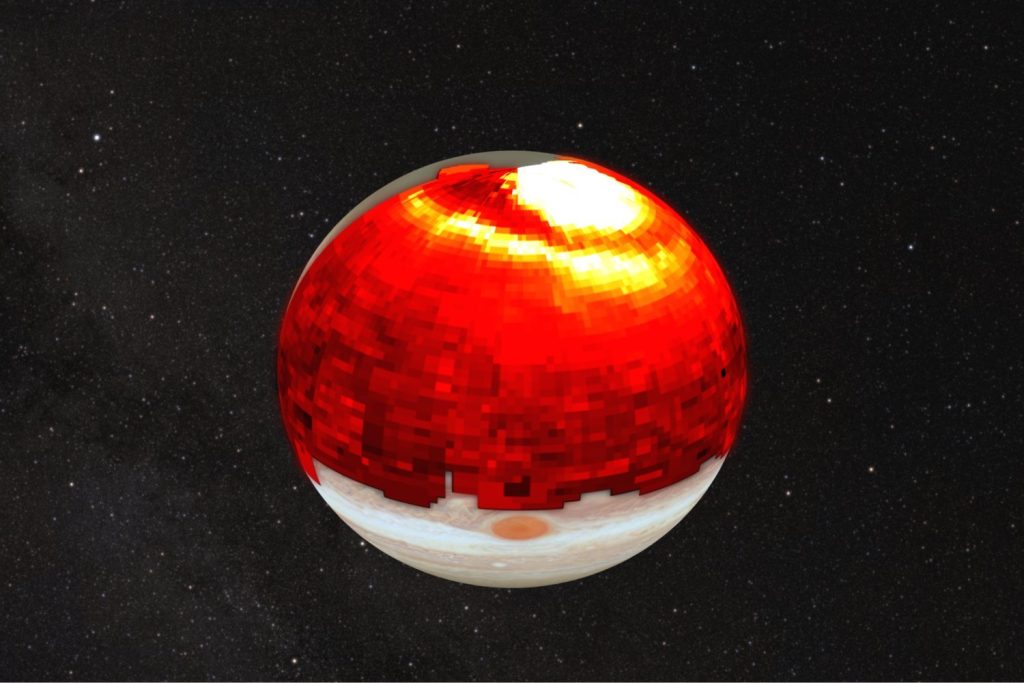

“We found that Jupiter’s upper atmosphere responds globally—and quite dramatically—to compressions by the impinging solar wind,” said James O’Donoghue, a planetary scientist at the University of Reading in the UK and lead author of the paper, in an email to Gizmodo. “A fast solar wind stream slammed into Jupiter’s magnetosphere, which acts like a giant magnetic bubble pushing back against the solar wind, triggering intense auroral activity which dumped heat into the atmosphere.”

The atmosphere around Jupiter’s poles then expanded, producing a thermal wave across the planet about 12 times as long as Earth’s diameter. The team managed to spot the event using data from the Keck II telescope and measurements taken by the Juno spacecraft above Jupiter, which happened to be “in the right place at the right time” to witness the event, O’Donoghue said.

Juno was within Jupiter’s magnetosphere up until the great squishing (as I’m calling it), at which point the compressed boundary suddenly put Juno outside of the magnetosphere. O’Donoghue added that astronomers have only seen similar heating on Earth—though on a much smaller scale.

“This may also happen at Saturn, Uranus, or Neptune, but we haven’t seen it yet,” O’Donoghue said. “It’s a rare event, though… compressions like this might reach Jupiter (or any planet) about a couple of times a month, depending on solar activity.”

“Our solar wind model correctly predicted when Jupiter’s atmosphere would be disturbed,” said Mathew Owens, a researcher also at University of Reading and co-author of the paper, in a university release. “This helps us further understand the accuracy of our forecasting systems, which is essential for protecting Earth from dangerous space weather.”

The research indicates that planetary atmospheres—including that of our solar system’s largest world—may be more susceptible to the behavior of host stars than previously known.

In our solar system, bursts from the Sun could change the atmospheric dynamics of the larger planets, generating winds that move energy throughout the worlds.

The work is also a reminder of how dynamic our Sun is, and how many solar system processes remain poorly understood. More observations, both of our host star and our solar system’s planets, will help scientists understand not only our solar system as an ecosystem, but also how similar—or unique—our system is from other star systems and exoplanets in the universe.