Roberta Bondar knew that she would not be able to hear birds, let alone seen them from space, but when she really thought about it, their absence struck her deeply.

So much so, that ever since becoming Canada’s first woman in space in 1992, Bondar has focused her cameras on natural environments, most recently in support of AMASS (Avian Migration Aerial, Surface, Space), a research project also known as “Space for Birds.”

“The idea that I could look down, look across the planet and just put myself in a mindset that I couldn’t see life and I couldn’t hear it was a jarring thought. When I came back, I wanted to photograph and try to share the importance of various environments on our planet to our life as human beings as we are on a planet and it would be kind of nice if we paid a bit more attention about conserving some of it,” Bondar, who on STS-42 also became the first neurologist in space, said in an interview with collectSPACE.com.

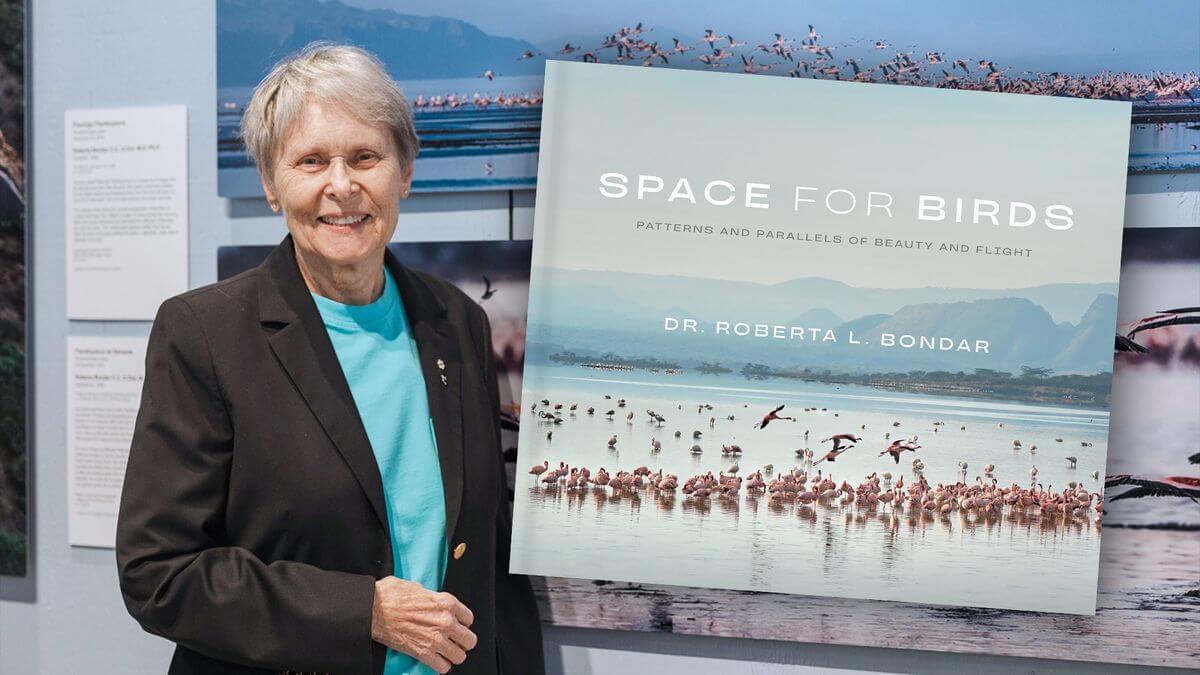

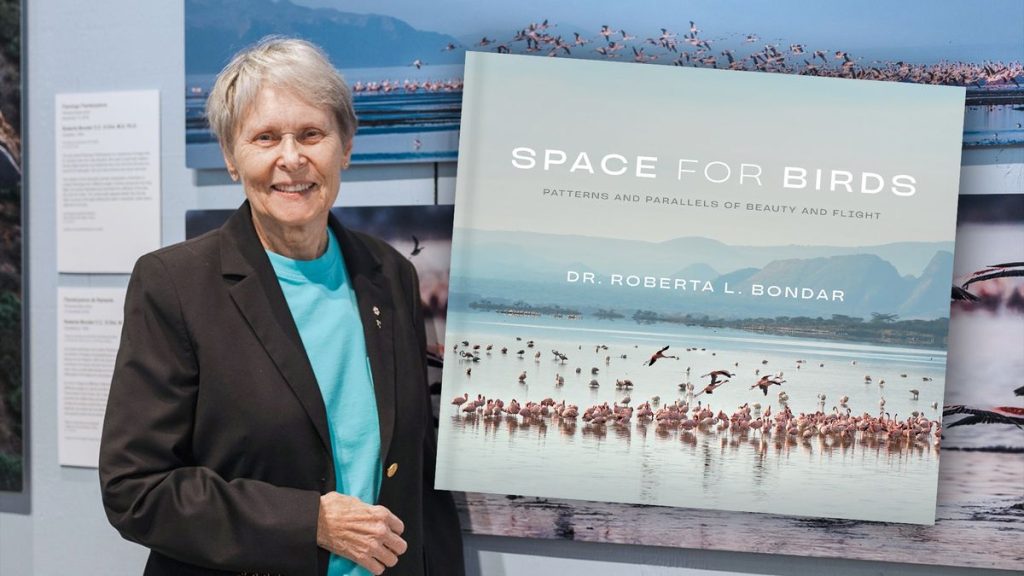

In “Space for Birds: Patterns and Parallels of Beauty and Flight,” released on Tuesday (Sept. 17) by Figure 1 Publishing, Bondar documents the lives and habitats of two of the international species that were chosen for AMASS. Unique to Bondar’s approach, she uses space-based imagery to provide the context for her ground and aerial photos as she tracks flocks migrating across the planet.

collectSPACE spoke with Bondar about the book, who it was written for and what she sees as the relationship between birds, Earth and spaceflight. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

collectSPACE (cS): Your other photography books are mostly about landscapes. What inspired you to focus on birds?

Roberta Bondar: I wanted to get back to one of my passions I had when I was young and that was flight and birds. So I quickly went back through my spaceflight and I realized that a lot of the things that I couldn’t hear were about the outdoors and nature.

Yes, there was some consideration about listening to my family’s voices, but for the most part, it was about not hearing things like bird sounds. They had always filled my world in Sault Ste. Marie when I was growing up. It filled my world anytime I went on hikes. These were creatures of the air, much in the same way astronauts are creatures of space.

So the idea of crossing boundaries without passports is something that I feel as an astronaut I had in common with birds.

cS: How did that connection translate into the narrative for “Space for Birds”?

Bondar: One of the things I wanted to do with my spaceflight was to have some kind of a visual story, not just to say, “Oh wow, look at the Earth. And that’s great. That’s great.” I wanted to have a story that talked about the life forms that were living on the planet that I couldn’t see.

It became very natural to try to look at flight corridors that migratory birds use. But because most of them are long distance migrants, you cannot grasp the whole thing by looking out the window of either a space station or the old space shuttle. The idea then, to me, was how could I develop a visual story that’s compelling for people emotionally, so they could see the application of looking at Earth from space as something to treasure and need to treasure on the surface of the planet while we’re down here. That’s really what I wanted to do.

cS: What led you to selecting the species of birds that you follow in the book?

Bondar: The first type of bird I selected was deliberate in the sense that when I was growing up in the mid-1940s in North America, there really only about 16 of these different creatures left, and there was a big conservation movement going on. So I remember hearing about them in school and then they finally found where they were nesting and now there are about 500 birds, which is not very many at all. So the whooping crane, itself, became quite a story about conservation.

And when I was thinking about trying to do this project, looking at their habitat from three perspectives, space was the obvious one, but the aerial shot is a little bit harder to comprehend, looking at their habitat relationships and how they manage in these habitats. You really have to pick a big bird — the whooping crane is five feet tall and it’s white.

The idea was to be able to see it in its environment and be able to try to capture it in an aesthetically pleasing way, so people would look at it and become quite engaged in the habitat. That was the challenge. Aerial photography is not for the faint of heart and for me, being a pilot, it was all about understanding the advantage of height it gives one. This is an advantage birds have as well, although I certainly see differently.

As for the lesser flamingo, so there is a huge distinction between the Western Hemisphere treatment, or what a bird does as bird behavior, compared to the Eastern Hemisphere. And the lesser flamingo with its completely different color, completely different types of habitat and completely different behaviors, it was really just extraordinary being able to compare the two. But they need the same thing. They need to have their habitat protected.

So that’s why the concentration on three perspectives: so that we can see a bird from the aerial perspective, not just look at the habitat itself, which we also include in the book, but also the bird in that habitat. The lesser flamingo is near threatened and the whooping crane is endangered, so I wanted to have a level of immediacy for the project such that people didn’t just think this was some random crow I was photographing.

The idea to have extraordinary creatures that live on the planet that I could photograph aerially and on the surface and make it a compelling story through artistic images was extremely important to me.

cS: Which is harder to master: photographing a point on Earth when traveling in orbit at 17,500 miles per hour (28,000 kph), or capturing a bird in motion from the air?

Bondar: Now that’s a good one. Capturing the planet and going so fast, it’s also about understanding the light and when it strikes the surface of the planet. But there’s a lot in there that you also have in an aerial shot of a bird.

The idea that birds will stay put is like the idea that the space station is not going to stay put. They’re not moving as fast, but relatively speaking, birds can decide, ‘Oh, I’m gone now,’ and take off and ruin something perfectly. You have all of the elements exactly where you want them and suddenly there’s no bird.

So I think they both have their challenges. It’s kind of interesting to say that space photography is more difficult than aerial photography of a bird, but in actual fact, they both have different challenges. I think people sweat through both of them.

cS: As your own photos capture, especially with the lesser flamingo, the birds can blanket a shore or the shallows of a lake with just a shade of light pink that almost becomes one unit. I know it’s impossible to see individual birds with space, but is there any evidence, like a color change, when seeing the area from orbit?

Bondar: One of the things that we can see from orbit on many different flights and be able to compare them — and this is different, obviously, than satellite imagery — is the ability of the habitat to change. And for the lesser flamingo, the food they feed on is this particular type of bacteria. It’s this bacteria that gives the lovely rosy color to their wings and their legs.

We can’t really see a lot of this from space, unless there’s a big mass of it, I mean huge masses. So when we look at the lakes where they birth, like Lake Natron in Tanzania, we see these large areas of these algal blooms as this very deep pink color. And we can see that change depending on the amount of water that is in the lake, that runs through the lake or runs out of the lake.

And that is what makes it very appealing to photography, to be able to see this — I refer to it as the many faces of Lake Natron. Because the flamingos, the reason why they are near threatened is that if anything happens to Lake Natron and this food source, it’ll wipe out 85 percent of the world population. So they’re living on the edge all the time, and it depends on the dilution of that lake. It depends on the amount of this bacterium.

That’s why, when we look at subsequent and sequential images through time, we are able to see that there are these things that are on the surface. Sometimes we don’t see the extent of them, because we need a much higher view in order to understand it. So although we don’t see the birds themselves, we see what their habitat is, and we see what it is that they require and the changes in that become quite dramatic. The loss of that really would reflect a potential collapse of this particular population of birds.

cS: For those who come across a copy of “Space for Birds” and do not know anything more about it then recognizing your name as an astronaut and seeing the title, but also noting the the cover image is of birds and not of Earth’s horizon as seen from orbit, how should they categorize the book? Is it a book about birds with space photography as a supporting tool? Or is it a space photography book that draws its focus from the habitat of birds?

Bondar: The back of the book does have an image of Africa from space where you can see the edge of the planet, so both components are on the cover. The question is a good one, though, because people try to pigeonhole things sometimes and there’s a point where one understands that there’s a thing called “application of knowledge.”

What I wanted to do was to use the aesthetic of the image from space to bring somebody into the story, but actually have the edge of Earth remind people that we are on a planet, and then say, “Why? Why is this important to see?” Because there is life down here. We can’t see it from space, nor what it looks like or what it needs in order to survive on this planet. We only get a cursory glance at that from spaceflight.

So I guess the direct answer is it’s an art photography book that deals with the subject of habitat, life and the planet basically through the eyes of human beings. And that’s something that, to me, is very, very emotional. That somebody actually saw this and photographed it.