Space sustainability is attracting far more attention than in previous decades.

“Historically, just getting people to think about it has been a problem,” said Marlon Sorge, executive director of the Aerospace Corp. Center for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies. “As challenging as it is keeping track of what everybody’s doing now, at least they’re doing something.”

Much of the increase in activity in low-Earth orbit, from 900 operational satellites in 2019 to about 10,000 today, has been driven by a single company: SpaceX.

“From an economics perspective, many of the risks are internalized to that company,” said Jamie Morin, Aerospace Corp. vice president of defense strategic space. “We’re about to go through a period where low-Earth orbit gets much more complex with probably two or three big [People’s Republic of China] constellations, at least one more U.S. big constellation, possibly some European big constellations and maybe even some African big constellations.”

Since no international agency oversees space traffic management, public and private organizations are devising their own sustainability strategies. Many were shared through papers and panel discussions at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Milan in October, where the theme was Responsible Space for Sustainability.

De Facto Standard

Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency JAXA is funding active debris removal.

Under a 12 billion yen ($78 million) JAXA contract awarded in August, Tokyo-based Astroscale is preparing to send a robotic spacecraft to low-Earth orbit in 2028 to grab the defunct H-2A upper stage that the company inspected during a precursor mission over the summer. The goal is to reach the rocket body and pull it into the atmosphere.

The Active Debris Removal by Astroscale-Japan 2 mission provides an opportunity to demonstrate new technology. It also may “set a de facto standard,” encouraging others to remove space objects and create a new market, said Ikuko Kuriyama, visiting researcher at the University of Tokyo Institute for Future Initiatives and senior JAXA administrator.

What’s more, active debris removal “will help the whole of the space economy to exist and maybe not to not exist,” said Hermann Ludwig Moeller, director of the European Space Policy Institute in Vienna.

Zero Debris

The U.K. Space Agency and the European Space Agency are also paying Astroscale UK and Switzerland’s ClearSpace to conduct active debris removal missions. In addition, many of Europe’s leading space organizations have joined ESA in signing the Zero Debris Charter, a non-binding agreement intended to prevent a net increase in space debris by 2030. To date, about 100 countries, companies and research organizations and international agencies have signed on.

“We issued an internal instruction for all ESA future missions to meet that goal,” said Frederic Nordlund, head of ESA’s European and External Relations Department. “It’s a very tough one.”

ESA’s technical requirements for reducing debris will be revised annually to guide managers toward the 2030 goal. In a related effort, ESA will send a small satellite to low-Earth orbit in 2027 to break apart.

“Why are we doing that? Because in that satellite we have 200 sensors that will tell us about reentry behavior,” Nordlund said. “We will share that information with everybody in order to meet the five-year reentry requirement.”

Name and Shame

Alongside space agencies, nonprofits are conducting space sustainability studies.

Mitre Corp. researchers presented a series of papers at IAC, including one that discussed how the lessons of behavioral economics could improve space security and sustainability.

“It’s providing incentives to the space actors to take a different route when it comes to designing space architecture or sharing information,” Zhanna Malekos Smith, professor for the United Nations Institute for Training and Research. “Our paper takes the position against heavy-handed regulation and encourages nudges, incentives, funding and public recognition.”

Through forums like IAC, it’s important to recognize “good actors for promoting international collaboration or sustainability as a way to reinforce positive norms,” Malekos Smith said.

It’s equally important to name and shame bad actors, said Mitre lead economist Thomas Groesbeck.

“Companies compare themselves to their peers,” Groesbeck said. “If you’re doing something that’s somewhat expensive and your peers aren’t doing it and they don’t suffer, you feel like a sucker. It’s important to either have some sort of honor for doing the right thing or some sort of shame for not doing it.”

Orbital Carrying Capacity

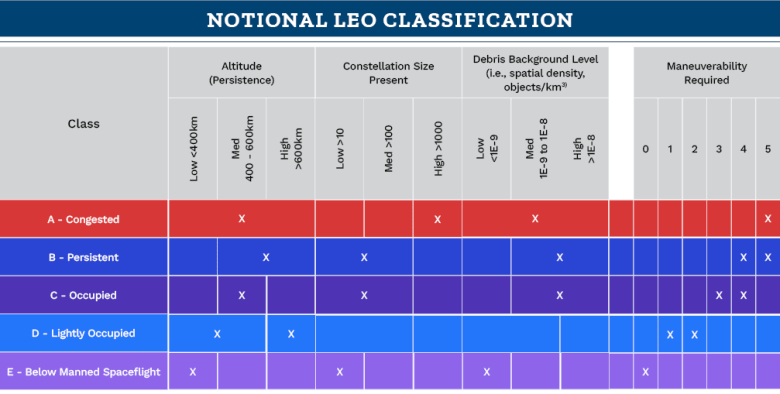

Another Mitre paper suggested altitude-based classes for low-Earth orbit along the lines of aviation airspace classes.

“Just in the last five years, we’ve gone from talking about a future with a few thousand operational satellites to one of tens or even hundreds of thousands,” said Ruth Stillwell, executive director of consulting firm Aerospace Policy Solutions, who worked as an air traffic controller for 25 years. “The issue of carrying capacity has landed squarely in our laps, but it is important to recognize that LEO is not a homogenous domain.”

The proposed orbital classification system would establish higher standards in areas of high demand.

“Like aviation, classification is not only a safety tool but can also be used as a means to increase carrying capacity of a defined orbital volume,” Stillwell said.

The proposed model calls for constellations with more than 1,000 satellites operating at altitudes between 400 and 650 kilometers to have robust maneuvering capabilities. In contrast, no maneuvering requirements would be placed on constellations of fewer than 10 satellites flying below 400 kilometers.

“Like aviation, it creates a means to establish higher standards in areas of high demand, while ensuring there are still opportunities available for less capable users to operate,” Stillwell said. “Another advantage of the airspace classification approach is that it is fully transparent, giving operators the opportunity to weigh the cost of increased capability against the benefit of airspace access in determining their mission profile.”

Cubesats and Constellations

The idea that regulations should vary based on satellite or constellation size came up repeatedly at IAC.

Morin pointed out that a university’s cubesat ejected from the International Space Station poses far less risk to space sustainability than a constellation of 10,000 commercial satellites.

“It makes a great deal of sense” that a constellation of 10,000 satellites “should be subject to significant scrutiny for the effects of those systems on sustainability,” Morin said. “But we don’t need to do that for everyone. If we did do that for the new entrants, we would essentially lock in the current participants and that’s unlikely to be helpful for the long-term dynamism of space research or the space economy.”

Moeller agreed that new requirements should be established to mitigate the risk that collisions pose to space systems and, in turn, to all the social and economic benefits people on Earth derive from space.

“We have the true requirement to put things into frameworks that you can only launch things if you comply with certain requirements,” Moeller said. It’s also important, he added, to ensure that any new requirements are “applied to the maximum extent possible across the oceans, in different world regions, so nobody is feeling handicapped.”

Global Rules

Establishing and enforcing global rules may prove difficult since there is no space counterpart to the International Civil Aviation Organization.

Stillwell suggested that launch states, which are responsible for authorizing and continually supervising the space activities of nongovernmental entities under Article 6 of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, could enforce an orbital classification system.

Even if states are not yet equipped to provide a high level of continuing supervision of satellite operators, “the concept can be developed within the existing treaty frameworks and grow to meet the demands of the industry it seeks to serve,” Stillwell said.

This article first appeared in the November 2024 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.