The astronomical confusion started at 2 a.m ET on June 26, 2023.

Scientists using the powerful James Webb Space Telescope sought to observe a planet beyond our solar system (an exoplanet) called Kepler-51d, an unusual “puffy” world with a cotton candy-like density. But it passed into view two hours earlier than expected. That’s strange for a planet, as they are usually quite predictable.

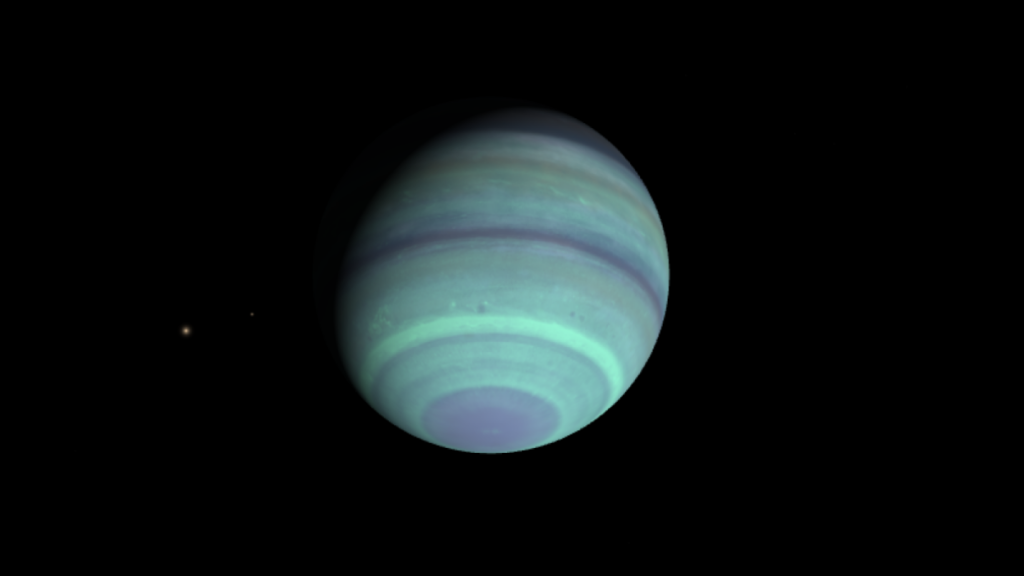

It turns out that a previously unknown world, and its potent gravity, altered Kepler-51d’s orbit. Now there are four known planets orbiting the sun-like star Kepler-51, located some 2,556 light-years away. And at least three of them are puffy.

“If trying to explain how three super puffs formed in one system wasn’t challenging enough, now we have to explain a fourth planet, whether it’s a super puff or not. And we can’t rule out additional planets in the system either,” Jessica Libby-Roberts, an astronomer at Penn State who led the observation, said in a statement.

The research was recently published in The Astronomical Journal.

Based on previous observations, the astronomers calculated that the distant world Kepler-51d would pass in front of its star on June 26, 2023, at 2 a.m. It was a valuable opportunity to use starlight shining through the planet’s atmosphere to reveal what’s transpiring on this mysterious orb. (This starlight passes through the exoplanet’s atmosphere, then through space, and ultimately into instruments called spectrographs aboard Webb, a strategy called “transit spectroscopy.” They’re essentially hi-tech prisms, which separate the light into a rainbow of colors. Certain molecules, like water, in the atmosphere absorb specific types, or colors, of light. If a color doesn’t show up for Webb, that means it got absorbed by the exoplanet’s atmosphere — revealing its presence.)

But nothing came at 2 a.m. “Thank goodness we started observing a few hours early to set a baseline, because 2 a.m. came, then 3, and we still hadn’t observed a change in the star’s brightness with APO [the Apache Point Observatory also used during these observations],” Libby-Roberts explained.

Their data, however, captured a dip in the star’s light around midnight. What could have caused the surprise orbital change? Only the gravitational influence of a large, previously unknown fourth planet, the researchers concluded. It’s now earned the name “Kepler-51e.”

“We were really puzzled by the early appearance of Kepler-51d, and no amount of fine-tuning the three-planet model could account for such a large discrepancy,” Kento Masuda, a study coauthor and associate professor of earth and space science at Osaka University, added. “Only adding a fourth planet explained this difference. This marks the first planet discovered by transit timing variations using JWST.”

Credit: NASA / ESA / L. Hustak / J. Olmsted / D. Player / F. Summers (STScI)

It’s unknown if Kepler-51e is a puffy world, too. Astronomers will need to gather valuable observations from a transit in front of its star. What’s known is that its orbit travels a little wider than Venus’ orbit around the sun, and dwells on the edge of its solar system’s habitable zone — a temperate region where liquid water could exist on a world’s surface.

Any puffy world is a curiosity: They might evolve, for example, into a super-Earth planet. In this star system, scientists already have at least three to continue observing. What will the fourth reveal?

The Webb telescope’s powerful abilities

The Webb telescope — a scientific collaboration between NASA, ESA, and the Canadian Space Agency — is designed to peer into the deepest cosmos and reveal new insights about the early universe. But as shown above, it’s also examining intriguing planets in our galaxy, along with the planets and moons in our solar system.

Here’s how Webb is achieving unparalleled feats, and likely will for decades to come:

– Giant mirror: Webb’s mirror, which captures light, is over 21 feet across. That’s over two-and-a-half times larger than the Hubble Space Telescope’s mirror. Capturing more light allows Webb to see more distant, ancient objects. The telescope is peering at stars and galaxies that formed over 13 billion years ago, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. “We’re going to see the very first stars and galaxies that ever formed,” Jean Creighton, an astronomer and the director of the Manfred Olson Planetarium at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, told Mashable in 2021.

– Infrared view: Unlike Hubble, which largely views light that’s visible to us, Webb is primarily an infrared telescope, meaning it views light in the infrared spectrum. This allows us to see far more of the universe. Infrared has longer wavelengths than visible light, so the light waves more efficiently slip through cosmic clouds; the light doesn’t as often collide with and get scattered by these densely packed particles. Ultimately, Webb’s infrared eyesight can penetrate places Hubble can’t.

“It lifts the veil,” said Creighton.

– Peering into distant exoplanets: The Webb telescope carries specialized equipment called spectrographs that will revolutionize our understanding of these far-off worlds. The instruments can decipher what molecules (such as water, carbon dioxide, and methane) exist in the atmospheres of distant exoplanets — be they gas giants or smaller rocky worlds. Webb looks at exoplanets in the Milky Way galaxy. Who knows what we’ll find?

“We might learn things we never thought about,” Mercedes López-Morales, an exoplanet researcher and astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics-Harvard & Smithsonian, told Mashable in 2021.

Already, astronomers have successfully found intriguing chemical reactions on a planet 700 light-years away, and have started looking at one of the most anticipated places in the cosmos: the rocky, Earth-sized planets of the TRAPPIST solar system.

TopicsNASA